In the process of exchanging perspectives on the materials shared in the HE, it became apparent that a significant portion of the site’s users were keenly interested in Bronze Age weaponry, particularly the arms and armor of the legendary Trojan War. The topic is undeniably intriguing, resonating with narratives familiar even at the level of a fifth-grade school textbook. Phrases like “Copper spears,” “Helm-helm Hector,” and “the famous shield of Achilles” evoke a sense of connection. Furthermore, this historical event itself is unique—discovered and explored through a poem, a true work of art. As individuals delved into the subject, they not only gained knowledge about it but also unearthed insights into a culture previously unknown to them.

.

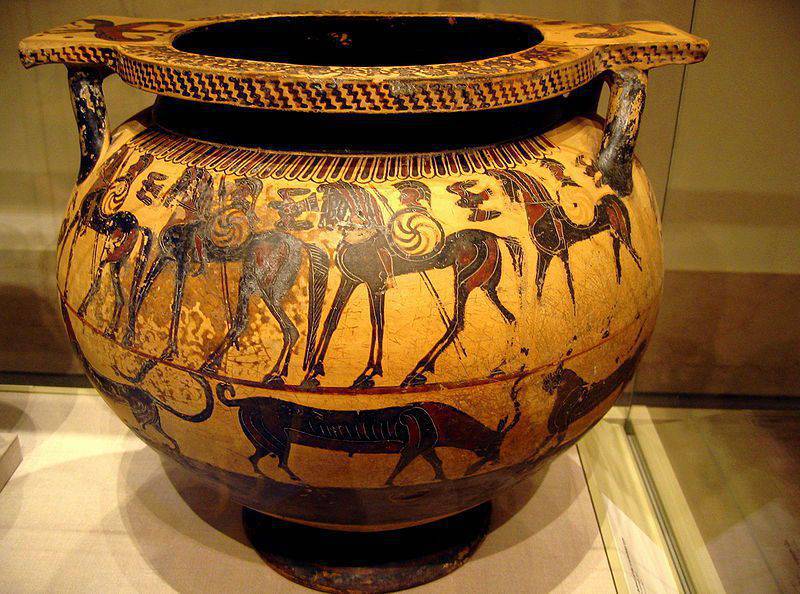

Black-figured ceramic vessel from Corinth depicting characters of the Trojan War (around 590-570 BC). (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Let’s begin at the start. The myth of Troy, besieged by the Greeks, lacked convincing evidence until the end of the nineteenth century. However, a turning point came when Heinrich Schliemann, fueled by substantial financial backing (having become wealthy), embarked on a quest to bring his romantic childhood dream to life. He set out to Asia Minor in search of the legendary Troy. By 355 AD, this name had vanished from all records. Undeterred, Schliemann, inspired by a vague description from Herodotus, directed his efforts towards the hill of Hisarlik and initiated excavations.

Over a span of more than 20 years, from 1871 until his death, Schliemann tirelessly dug at the site. Yet, as an archaeologist, he was unconventional. He extracted artifacts without documenting them, discarded anything he deemed unimportant, and relentlessly dug and dug. Finally, his perseverance led him to discover what he believed to be “his” Troy.

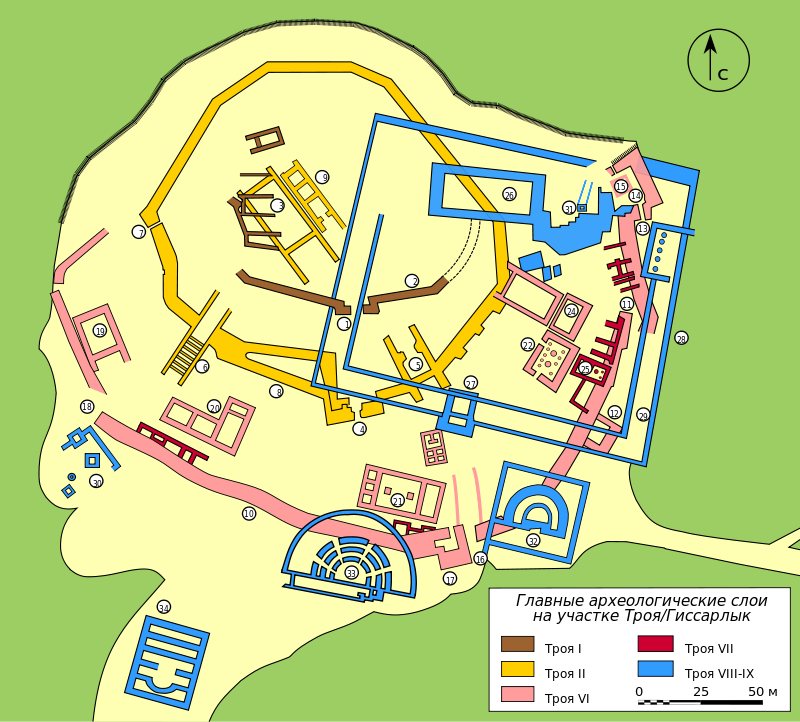

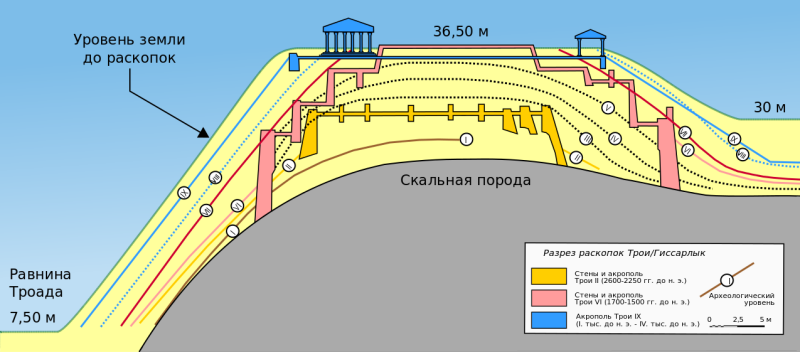

Many scientists of that era harbored doubts regarding whether this discovery was indeed Troy. However, with the support of British Prime Minister William Gladstone and the inclusion of professional archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld in his team, the veil over the secrets of the ancient city began to lift. The most surprising revelation was the identification of multiple cultural layers, signifying the construction of a new Troy atop the remnants of the previous one each time.

These layers, numbering as many as five, showcased the evolution of the city over time. Troy I, the oldest, contrasted with the “youngest” Troy IX from the Roman era. Presently, the archaeological site reveals even more layers and sub-layers, totaling 46. This abundance of historical strata posed a considerable challenge in deciphering the specific details of Troy’s history.

Schliemann believed that the Troy he sought was Troy II, but, in reality, the authentic Troy is identified as Number VII. Substantial evidence supports the conclusion that the city met its demise in the flames of a fire, and the remains of individuals discovered in this layer tell a poignant tale of a violent death. The year associated with this catastrophic event is widely considered to be 1250 BC.